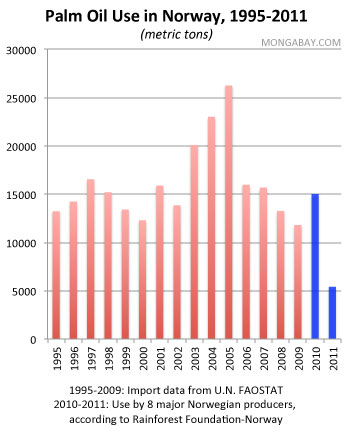

Campaign cuts Norway’s palm oil consumption 64%

mongabay.com : July 25, 2012

A campaign run by environmental activists has helped lead to a 87 percent reduction in palm oil use by eight major food companies in Norway, reports Rainforest Foundation Norway, which led the effort.

Rainforest Foundation Norway and Green Living launched the palm oil campaign last fall highlight links between palm oil consumption and deforestation in Southeast Asia. It aimed to reduce demand for palm oil in the Scandinavian country, where palm oil consumption was roughly 3 kilogram per year, mostly through processed food products.

The campaign asked major food companies to disclose their palm oil use and whether palm oil was certified under the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO), an eco-certification initiative. Following the survey, the environmental groups published a ‘palm oil guide’ where consumers could look up the palm oil content in the products they buy. The effort went beyond traditional labeling which allowed palm oil to be listed generically as ‘vegetable oil’ or ‘vegetable fat’.

According to Rainforest Foundation Norway, the campaign had an immediate impact — Norwegian food producers started to scale back on, or even phase out, palm oil. Stabburet, which was once one of the country’s largest palm oil buyers, banished palm oil from its products completely, while Mills, the largest buyer, cut use by 95 percent. The result so far is food companies in Norway have reduced palm oil buying by 9,591 metric tons, or 87 percent of last year’s 11,052 tons worth of palm oil. With the eight companies accounting for roughly three-quarters of Norway’s total palm oil use for food products, per capita palm oil consumption in Norway is set to fall to just over 1 kilo per year.

The campaign only targeted food manufacturers, not fast food chains and restaurants, cosmetics producers, or animal feed makers.

Lars Løvold, Director of Rainforest Foundation Norway, said the campaign could be a model for other countries.

“Norwegian food producers have demonstrated that it is possible to produce and sell food without palm oil, avoiding complicity in rainforest destruction,” said Løvold. “The experience from Norway should inspire consumers globally to demand food products which do not contribute to rainforest destruction.”

Palm oil is the most productive of commercial oil seeds but its expansion in recent decades has taken a heavy toll on rainforests and peatlands in Indonesia and Malaysia, which account for nearly 90 percent of global production. Green campaigners have thus targeted major palm oil buyers in an effort to shift the industry toward less damaging practices. In response, the palm oil industry, working with some environmental groups, have set up the RSPO which sets social and environmental criteria for palm oil production. The hope is that buyers are willing to pay a slight premium for RSPO-certified palm oil. Still some activists have criticized the RSPO as not being strong enough and are campaigning for stricter safeguards.

The palm oil industry asserts its crop offers more oil per unit of area than other oilseeds, reducing the need to clear forests relative to other crops. But that argument has failed to win over environmentalists who note that forest clearing for oil palm plantations has not slowed and is now expanding to other parts of the world, including West Africa, Central and South America, Papua New Guinea, and the South Pacific.

Norway is one of the world’s largest supporters of tropical forest conservation. It has committed three billion Norwegian krone ($500 million) per year to slowing deforestation, including billion dollar pledges to Indonesia and Brazil for forest protection programs. The country’s pension fund nevertheless continues to invest in companies associated with forest conversion, a sore point for activists.